Launching a New Era in Mitochondrial Gene Editing

Launching a New Era in Mitochondrial Gene Editing

From his early days studying science to decades of dedicated research in mitochondrial DNA and gene therapy, Dr. Carlos T. Moraes has made an indelible mark in his field.

After studying biomedicine and molecular biology in São Paulo, Brazil, where he was born and raised, a young Carlos jumped at an opportunity to connect with an esteemed neurologist, an expert in neuromuscular diseases including mitochondrial disease, in New York. Shortly after arriving and completing a stint of training with the neurologist, he decided to pursue a PhD at New York City’s Columbia University.

“This was back in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and it was a pretty exciting time,” says Dr. Moraes. “Mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) were just being reported for the first time. The neurologist I was studying under (Dr. Salvatore DiMauro) had many muscle biopsies that we could analyze, and one of the first things we did was correlate certain mutations with certain disease phenotypes. One paper we published early on was about how large deletions in mtDNA were almost always found in patients who have Kearns-Sayre syndrome, a rare neuromuscular disorder.”

As more mutations were reported, the field of mitochondrial genetics exploded. Dr. Moraes completed his studies in New York and took a research facility position at the University of Miami in 1994, where he remains a prominent professor in the Department of Neurology at the Miller School of Medicine. “I continued to study mtDNA problems, not only in disease but also in aging,” he says, “with mtDNA always being at the core of it.”

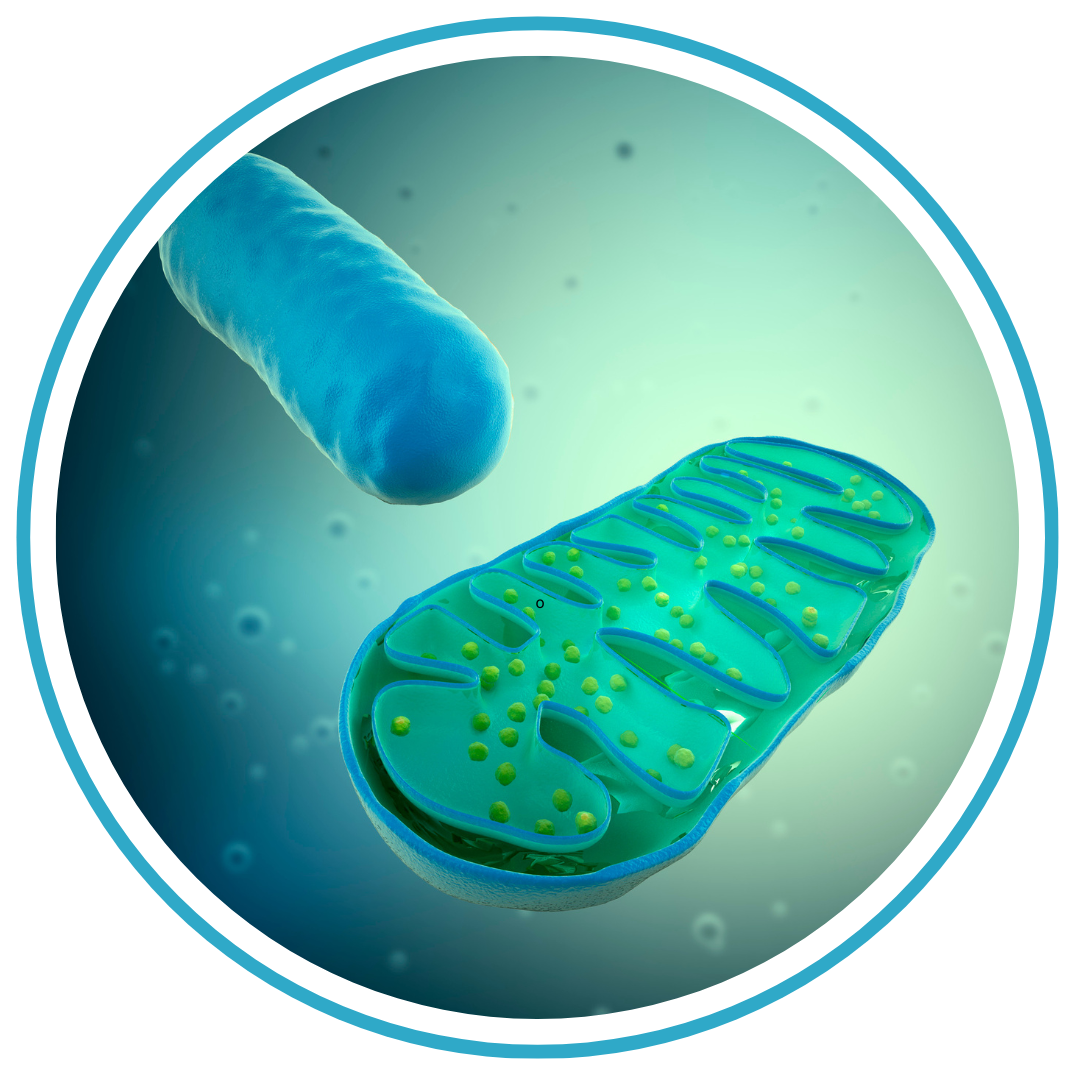

Sometimes happenstance brings about the most meaningful paths. “I started working on mitochondrial diseases by pure chance, but the more I worked on it, the more I fell in love with it,” says Dr. Moraes. “The mitochondrion is like a battery inside the cell, and it has its own DNA. It’s the only organelle besides the nucleus that does. It’s a fascinating system, and so I’ve devoted my career to it.”

Sometimes happenstance brings about the most meaningful paths. “I started working on mitochondrial diseases by pure chance, but the more I worked on it, the more I fell in love with it,” says Dr. Moraes. “The mitochondrion is like a battery inside the cell, and it has its own DNA. It’s the only organelle besides the nucleus that does. It’s a fascinating system, and so I’ve devoted my career to it.”

Dr. Moraes was also driven by a desire to help patients living with mitochondrial disease. “I’m not an MD, but very early on I was touched by the lack of treatments these patients had,” he says. “That was extra motivation to work more and more toward therapy.”

Continuing his research, Dr. Moraes and his colleagues found that a specific genetic mutation, usually responsible for mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), also caused a variety of manifestations. “This mutation is one of the most common mtDNA mutations in the patient population,” he says. “In 1993, we published research showing that patients with this mutation could have many different types of diseases and many different symptoms, and that these symptoms clustered within families, suggesting that nuclear DNA plays a role in modifying how the mtDNA mutation shows up.”

Continuing his research, Dr. Moraes and his colleagues found that a specific genetic mutation, usually responsible for mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), also caused a variety of manifestations. “This mutation is one of the most common mtDNA mutations in the patient population,” he says. “In 1993, we published research showing that patients with this mutation could have many different types of diseases and many different symptoms, and that these symptoms clustered within families, suggesting that nuclear DNA plays a role in modifying how the mtDNA mutation shows up.”

Building on this research, Dr. Moraes conducted an evolutionary compatibility experiment. “We took mtDNA from different types of primates and put it into cells with human nuclear DNA to see if they could produce energy,” he says. “The only mtDNA that could coexist with human nuclei was from chimpanzees and gorillas.” Even an orangutan’s mtDNA wouldn’t work. “They co-evolved with enough difference that they cannot work together,” explains Dr. Moraes. The experiment showed how closely mtDNA and nuclear DNA must work together, and how that relationship was shaped by millions of years of evolution.

In the last two decades, Dr. Moraes’ research has focused more and more on gene therapy and on pioneering mtDNA gene editing techniques. “One thing I’m known for is using enzymes that cut mtDNA as a form of therapy,” he says. “In the lab, we use these enzymes called restriction enzymes. They recognize a short sequence in the mtDNA and cut it. They’re very specific. They cut only on this sequence. This was in the early 2000s.”

Further research and genetic engineering demonstrated that when mutant mtDNA was targeted and cut, the remaining healthy mtDNA would take over. “We showed that once we cut the mtDNA, it’s very quickly degraded, and whatever’s left replicates to make up for the loss,” says Dr. Moraes.

The restriction enzymes were limited, however. While they were capable of cutting out mutant mtDNA, “there aren’t many disease mutations that create restriction sites for these enzymes,” says Dr. Moraes. “We were always thinking, if only there was an enzyme that didn’t only recognize such small sequences, but also bigger ones. If only there was a way we could control this enzyme.” They needed something programmable.

“Our dreams came true around 2010, when gene editing enzymes were first described,” says Dr. Moraes. “They could be engineered to recognize long, specific sequences, and more importantly, you could design what kind of sequence you wanted them to recognize.”

These new protein-based gene editors changed the game, allowing scientists to target almost any DNA sequence. “That was a major breakthrough that allowed us to eliminate mutant mtDNA in a very specific way,” says Dr. Moraes. “And again, as the mutant mtDNA was cut, the normal mtDNA that was left would replicate to make up for the lack of mtDNA quantity. This would change the cell, causing it to behave better and to produce more energy.”

Next, Dr. Moraes and his team started collaborating with Precision BioSciences, a company that had developed novel gene editing enzymes called ARCUS and mitoARCUS. These enzymes were smaller and easier to deliver to the cell. “We continue to collaborate to this day,” says Dr. Moraes.“They’re now trying to perform a clinical trial on mitoARCUS that’s specific to the mutation that’s usually associated with MELAS, but also associated with exercise intolerance and other symptoms like hearing loss, diabetes, and migraines.”

In 2020, researchers discovered mitochondrial base editors, which can change a single letter of mtDNA without cutting. “They’re called base editors because they edit the DNA,” says Dr. Moraes. “A base editor that works in the mtDNA was able to change a C to a T in the DNA code. It was very limited, but it was the first step. For the first time, we could change mtDNA without having to cut.”

Expanding on this research, Dr. Moraes and his lab used one of the base editors to rescue mitochondrial function in a mouse model. “We found a way to base edit a gene with a pathogenic mutation so that it became stable, improving the function of the mitochondrial energy production in the mouse model,” he says.

research, Dr. Moraes and his lab used one of the base editors to rescue mitochondrial function in a mouse model. “We found a way to base edit a gene with a pathogenic mutation so that it became stable, improving the function of the mitochondrial energy production in the mouse model,” he says.

Those familiar with the gene editing technology CRISPR may wonder why it’s not part of the story here. “I’m always asked why we can’t use CRISPR to cut or edit mtDNA,” says Dr. Moraes. “CRISPR needs a guide RNA, and we don’t know how to make RNA go to mitochondria, so it won’t work.”

While both nuclear gene therapy and mtDNA editing have advanced greatly, Dr. Moraes notes that the main limitation is the difficulty of getting the gene editing tools into the cells that need them. Progress continues to be made; however, scientists push forward with new strategies to overcome these delivery challenges.

“If you reduce mutant mtDNA below a certain threshold that makes a patient sick, you’re essentially curing the disease,” says Dr. Moraes. “So this is potentially curative.”

He also notes the exciting potential of a one-and-done solution. “If you reduce this mutant mtDNA enough, probably you don’t have to do it again,” he says. This is in contrast to nuclear gene therapies, as are used for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example, where the treatment effect can diminish over time and repeat dosing is challenging.

Dr. Moraes loves working with students, trainees, and technicians, describing his work as exciting and rewarding. “I love everything about it,” he says. “And it goes without saying that if we can find something that can help patients, that’s at the top of the list of the rewards we’re looking for.”

The motivation to continue developing these therapies and finding treatments or a cure is strong. Dr. Moraes encourages the next generations of researchers to have  a thick skin and to be tenacious. “We have to keep pushing,” he says. “There are lots of failures in this field, but a failure isn’t a total failure if you understand why the experiment didn’t work. It always teaches you something.”

a thick skin and to be tenacious. “We have to keep pushing,” he says. “There are lots of failures in this field, but a failure isn’t a total failure if you understand why the experiment didn’t work. It always teaches you something.”

With the field of gene therapy exploding, Dr. Moraes is extremely optimistic about the future, mentioning that he expects that a major gene therapy breakthrough is “just around the corner.”

He’s pleased to share his research with the MitoCommunity as well. “It’s very important for science not to live in a silo, isolated from the community that it’s trying to help,” he says. “The MitoCommunity needs information, and to help us keep doing our work. Research is a very expensive business, unfortunately, and it cannot be done without funding. We need patients, families, and scientists working together to keep the field moving forward.”